FFT Düsseldorf

The Year 2017

A Collective Chronicle of Thoughts and Observations

Welcome to what is going to be a collective chronicle of the year 2017! This journal will follow the general change that we experience in our daily lives, in our cities, countries and beyond, in the political discourses and in our reflections on the role of artists and intellectuals. Originating from several talks and discussions with fellow artists and thinkers FFT feels the strong need to share thoughts and feelings about how we witness what is going on in the world. Week after week different writers, artists, thinkers and scientists will take the role of an observer as they contribute to this collective diary.

#43 October, 23rd - 29th

Jeannette Mohr

23. October 2017

I will probably for ever remember the view from the inside of my house, through the yellow screen door, here in Burkina Faso: the red earth, the sparse grass, some stones, a brick laying on a modest mound, a tree and branches of others, the roofs of two of the teachers’ houses up on a hillside across from me and the milky blue sky over the Operndorf Afrika.

We, Claus Föttinger, Mouhamadou Moustapha Diop and I, are here as this year’s artists in residence at the Operndorf, about 30 Kilometers North of the capital Ouagadougou. Opera village, Operndorf – it’s utopian, a symbol for what can happen when someone shows perseverance, an idea that materialized in the reality of here and now. “Here” is an open space on the countryside. There are houses built, a school, a hospital and there still is a big empty space in the middle. No opera house, no opera in the traditional sense, no Wagner, no Händel, no Mozart. I don’t think at all that this is missing. The “opera” here is what is taking place daily. Between the people who live and work here, in the Krankenstation where toothaches can be remedied, primary care is provided and women can give birth, in the classrooms where the children of the surrounding villages learn, inside the houses where nurses and teachers live, in the studios of the artists, and in the kitchen and the canteen where food is freshly prepared every school day and the kids eat. And on this spare, empty place in between.

I once saw an installation by the Canadian artist Dominique Blain at the LACMA, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art that this open space suddenly reminds me of. In one of the museum’s rooms, seven human shaped figures in black veils were sitting in a circle on the floor. At first they looked like monks or women wearing chadors or nomads sitting around a campfire in a desert. But then I realized that the figures were hollow. In spite of their hollowness, they radiated an enormous physical presence. Like ancestral figures in an archaic ceremony, these “bodies” were arranged close to each other and it seemed as if they were involved in silent communication or some kind of collective meditation. The inside of the circle was empty and the “heads” of the “bodies” were aligned in such a way, that assuming these figures had faces and eyes, their gazes were going to meet in the exact middle of the circle. As a result the center of the circle seemed highly charged with energy. The figures surrounding the empty space appeared to share a common interest and to revolve around a common center. The figures were hollow, the space in the middle of the circle was empty and yet, in all its absence, there was something present.

This is how I feel about this place here. About this empty space in the middle of the Operndorf. There is something present already. In a rendering of the whole project by its architect, Francis Keré, stands right in the middle the model for a “Festspielhaus”, a place for cultural encounters. But to me it seems already enough that the place is defined, dedicated and spoken for.

Suddenly I’m reminded of how a circle drawn with a piece of chalk can indicate an area for theatre to happen. Once you step inside the circle, you become part of the performance.

For the next five weeks I will have the unique opportunity to work with ten of the children that go to school here. We will create, dream and play theatre together. I’m nervous. Will I be able to motivate the kids? Will I be able to provide the circumstances that they feel safe and self confident enough to dare to play? Will they “talk” to and with me? Will it be worthwhile for them?

24. October 2017

I made it. In the afternoon the kids came running - cackling, jabbering and laughing - to our first gathering. In the morning I had met the ones that Abdoulaye Ouedraogo, the director of the school, had chosen for me, for a first “hello” at his office. I had taken pictures, one with and one without him that were now hanging on the wall. Immediately the children investigated the prints. “That’s me”, they called out when they spotted themselves. Then they giggled and continued to check out the space that I had set up.

In search of a good place where the kids and I could assemble for our theatre meetings, I had wandered the premises the day before and had found a nice shady place between the canteen and the building where the lunch benches are stored, with a pleasant draft and several posts where I could clamp some cloth lines to attach pictures.

We will be meeting three hours a week. Although that is not much time to develop a dramatic piece or a performance it will give us ample opportunities to play with each other. We will get to know each other, tell stories about us and find out about what makes us tick, what makes us similar and what different. Today one of the girls touched my hair to see how it feels and how my curls are different from hers. A boy checked the white skin on my arm with its red bumps from all the mosquito bites I got. I had to think about how these gestures of curiosity are only possible in our close encounter with each other here and how different they would be perceived were they reversed and taken out of this context.

During the last two weeks I participated in the music and theater courses at the school. The kids, especially the girls, seemed to me somehow shy and holding back. Today I was surprised about the abundance of energy they all showed – but then, maybe I already got the “stars” to play with? After an hour I was exhausted but happy. We all had fun, we learnt something about each other and tomorrow we will continue.

In the evening I cooked some pasta on our terrace, a tin roofed open space on top of “my” house, overlooking the surrounding savanna. From there I can see the children arriving to school in the morning and in the afternoon I can watch them leaving. Sometimes they linger and play with our empty plastic water bottles – a sought after commodity – at the fountain. Claus had bought a radio in Ziniaré, the next village, about 5 Kilometers North and now the sound of Radio Ouagadougou rang into the night. Prosper, one of the guards at the Operndorf paid us a visit and he and Claus started to dance.

25. October 2017

Today I drove to Ziniaré to get some money and run a few errands before our weekend trip. Tomorrow we are invited at a reception at the residence of the German Embassy in Ouagadougou to celebrate the day of German Unity. Since we planned a weekend trip to Bobo-Dioulasso, the second biggest city of Burkina Faso and to Banfora, about 450 Kilometers in the South, close to the border to the Ivory Coast, we’ll be staying the night in “Ouaga” at a quaint little hotel from which a driver will pick us up Friday morning.

I love to drive our beat up pick up truck on small trips, because it makes me feel independent, self -determined and part of how the world moves. Out here, on the countryside, the means of transportation are typically carts hauled by donkeys, bicycles, scooters and two wheeled wagons pulled by a scooter. It is not unusual to see a woman, veiled or not, sitting on the iron frame of a donkey cart, holding a mobile phone, checking something or making a call while the cart is slowly drawn by the donkey. This side by side or better, the simultaneity of different stages of development is still mind boggling to me.

Although Ziniaré is a district capital, birth place of former President Compaoré – who, three years ago, was ousted from office by a revolution, after he tried to change the constituion to prolong his term ad ultimo - there are only a few tarred roads. Kiosks, stalls and shops line the roads where all kinds of goods are offered. Fuel in glass bottles; school books, paper and pens; watermelons, yams, papayas and tomatoes; “pièces detachées” - spare parts for scooters and cars; mobile phones, phone cards and phone accessories; backpacks and soccer uniforms in gleaming colors; and everywhere – outposts of “orange money”- a mobile money service that is widely used not only in Burkina Faso but in at least 16 other African countries and since 2016 also in France.

It’s hard to believe that it’s already more than three weeks that I arrived in Ouagadougou. It has been three weeks of changing perspectives, changing the lenses of perception almost daily, changing what and how I see it. I have developed some routine, found out where I can get what I need for the daily living and for my work. Once in a while I drive to Ouagadougou, which is always exhausting. It’s only a one-hour drive, but the heat and the dust make it excruciating. Today, Diop, our fellow artist from Senegal is not feeling well and shows signs of exhaustion. It’s no wonder, since he has ridden his roller to Ouagadougou almost daily to collect material for the film he’s making here.

I feel moments of immense fatigue, too. Moments when I’m tired of the dust, tired of the heat. Tired of seeing tired bodies, tired of seeing how hard live is here, tired of seeing how much effort it costs to just live. And then I feel guilty because this is utterly self indulgent, a damn white privilege. I can always just book a flight, board a plane and go back to my cozy, almost dust free, white life. And then I think of the children here, of the optimism they spread and the perspective that things may be able to change for the better through education and that I entered into some kind of social contract, that I made a promise to me and to these kids, that I committed to here and now. By then, it still will be dusty and electricity and water sporadic, the Internet spotty – but I fill have found my bearing again.

26. October 2017

In the afternoon Claus and I drove to Ouagdougou, to the same hotel where we spent our first night in Burkina Faso. What a different experience it was to arrive today compared to my first night in Ouaga!

Then, our flight was delayed and we arrived after midnight. Severin, the Program Manager picked us up and drove us to the hotel. Driving through Ouagadougou at night shocked me. It was dark and streetlights were almost nonexistent. We drove over red sand tracks full of potholes and I had nothing for orientation. Barely held up kiosks and shacks lined the sides, just about secured with cardboards and corrugated metal; people, mostly men, slept on sidewalks and in front of stores; a few multi storied concrete construction projects were abandoned and seemed like ruins, even before their completion; overall the city, or what I could perceive of it, seemed a horizontal, wide spread chaos; there was almost no lighting except the eerie flicker of neon tubes or of one or two quivering neon letters of a store’s name; countless scooters shot by, driven without lights; prostitutes were walking the dark streets and undressed, headless mannequins stood inside storefront windows; and above all was the sweet smell of decay, exhaust and burned wood – to me, it was dystopian. When we arrived at our hotel it was pitch dark and it seemingly took forever until someone arrived at the gate, pointing the faint blue beam of a flashlight in front of them.

As it happens the hotel is very nice and was very nice then. But I was so disoriented and definitely out of my comfort zone when we arrived three weeks ago that I had no capacities of seeing it then. How different one place can appear at different times, depending on nothing but how you feel at the moment - your gaze totally influenced by your current state of mind.

Ouagadougou has not really changed in my perception although it is less intimidating by daylight. Still, the ubiquitous pervasive dust, the relentless chaos and the daunting traffic with its countless scooters and bicycles that are every where, left and right, before and behind you, are flat out exhausting.

We spent a few hours relaxing in the hotel before a cab picked us up for the reception at the residency of the ad interim German ambassador. Our cab driver could not immediately find the residence and in heavy traffic we drove up and down one of the big boulevards before we dove into various dark alleys in search of our destination until we saw a sign that we could follow. This street was a dirt road, bumpy and dark, too, almost unlit, but the size of the properties left and right with their huge walls, barbed wire on top, made it clear that we were in an official part of the city. After another turn, the end of the road was suddenly gleaming under floodlights and completely closed off with roadblocks. Heavily armed soldiers patrolled everyone who wanted to pass. The military presence not only in the capital but also all over the country is certainly due to the latest attack by Islamist extremists and the insecure situation in the North at the border to Mali.

It was interesting to see how Germany presents itself in and to Burkina Faso. The reception was held in the residence of the ambassador, between private living and representation, a surprisingly inconspicuous affair. The dress code was relaxed and allowed Dirndl and Lederhosen as well as official Burkinabe attire. Besides German beer that was served in jugs, French wine was offered, maybe as a nod to Burkina’s colonial past. As a friendly gesture, a choir of young Burkinabe girls sung first the anthem of Burkina Faso and then the German one. The invitation list showed consideration to the present and the past, officials from both sides of the aisle were invited. Germany keeps a neutral position. The bishop of Burkina Faso, capped and gowned, was present as well as chiefs, other officials and important dignitaries and some Soufi representatives in colorful dresses and equally colorful turbans.

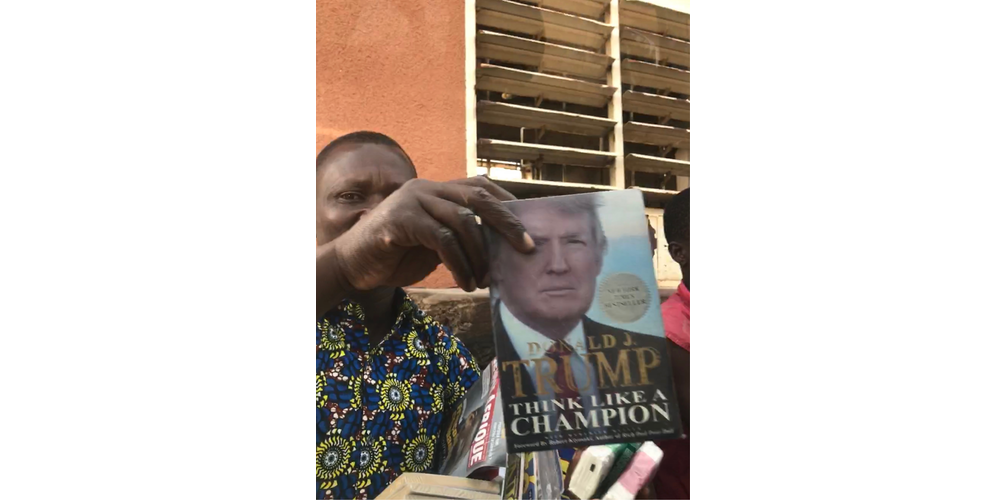

I had to think about all the things that happened this year and the places I have been. I lived in the US when Donald Trump took office, I was in Turkey when Erdogan imprisoned people, I was in Germany when Helmut Kohl was buried and a few months later when the AfD received 14% of the vote. Now I’m in Burkina Faso and amidst al this dust and effort I suddenly feel at ease and I dance...

27. October 2017

I fell asleep with my laptop next to me, my hand on its closed top as if I could will the story of the day to miraculously type itself. Today we drove eight hours, from Ouagdougou to Banfora in the southwest corner of Burkina Faso. About 50 Kilometers further South is the border to the Ivory Coast.

Eight hours in a car with pictures and images streaming by in in a continuous flow. We take photo after photo, the clicking of Claus’ camera providing the soundtrack. Each image works like a still, so much information encrypted, hard to decipher - the shacks, the storefronts, the signs with their touchingly simple drawings, the villages with their round, straw covered reservoirs, the children under trees, the women at the fountains, the men at the bars, the loaded mini buses, the fabrics of the clothes. Everything has meaning, every little detail tells a story.

At a traffic light a women on a scooter stops next to us. The print of her skirt is green black, yellow and white. In a repeating pattern of oval medallions a women is drawn in the middle, holding a girl on her hand, an inscription surrounding the drawing that reads: “ 08 Mars Journée Internationale de la Femme” and underneath “non a l’exision”. No to circumcision, no to female genital mutilation, which supposedly, although there is a law against it, is still at least at a 50% rate in Burkina. The woman smiled at me when I took the picture.

Picture taking is not always welcome. In Houndé, a little town on the way, a market took place. Because of the market day lots of women were on their way to Houndé, mostly in the back of two-wheeled carts, drawn by scooters, which were usually driven by a man. The women were sitting in the back of the carts in groups, in their colorful outfits, quite a few carrying little children wrapped in scarves on their backs. They were not always happy when their picture was taken and from their demeanor they made it clear that it was understood how they thought about this perceived violation. The wording in English and French gives it away – the photographer takes something, “on prend une photo” without giving something back. A picture is “stolen”. In a lot of places here in Burkina Faso one has to pay a fee for taking pictures, a lesser fee for smart phones, a larger fee for professional cameras. Often even an official permission is needed. But how does that make it “right”? As my friend Mariana Ortega, a philosopher in the US wrote to me not too long ago, after I posted a picture of a group of older women in Turkey, sitting together on the side of a market - “be mindful of the gaze that relegates women from other countries as different, weird etc. and that invites comments of how poor the are. This is a colonial gaze as they haven’t been asked to be part of our gaze”. I felt misunderstood, had I not taken this picture because I loved the community of these women? But still, the question resonates with me and I wonder - how can you avoid that gaze?

Every image is loaded with information. Layer upon layer. Sometimes I forgot what I have seen until I sift through my pictures in the evening. They help me to remember and I can look closer than I would otherwise be allowed to.

I look at a picture of an overloaded minibus, the preferred means of transportation for many on longer hauls. A wonderful buildup of objects, belongings and freshly made purchases - packages, bikes and scooters, sacks filled with grains, plastic bowls, furniture, cages with chickens, boxes, suitcases – what doesn’t fit on the roof – and a lot fits on these roofs! – is pressed and pushed in the back of the bus. And then I see it - at the end of the packing, some guys must have climbed up on top of this unlikely to hold up pyramid and now they took a nap on the drive, human “cargo” blending in with the rest of the load.

The day ends with a simple image. A beautifully hand carved little wooden tray with two small indentations for pepper and salt. But even that is more than just an image, even that has meaning. Black and white. Noire et blanc

28. October 2017

The day starts with a sensation – I can actually congratulate my mother to her birthday via Facetime, the Internet connection at the hotel proofs stable enough! My mom is happy to talk to me, to see me, but I’m somewhat disappointed that she can’t grasp the improbability of this connection – from Banfora to Nürnberg in an instant. That she shows no sign of understanding how far away I really am. But how could she, when even I forget it in a moment like this. I make our driver and Claus shout happy birthday in French and we both are quite happy.

The day continues with a string of beautiful moments - a quiet ride in a simple wooden boat over a lake to see hippos; a handmade crown of sea lilies on my head; spotting golden sneakers on the feet of an elder who is sitting in the shade of a tree; crawling into a 500 year old sacred baobab tree; climbing up the peaks of Sindou, needlelike formations shaped by wind erosion; and seeing the cascades of Karfiguela, a series of waterfalls close to Banfora.

At the end of the day I’m so exhausted that I get the chills and shiver in spite of the 38° degrees inside and outside. But once I crawl under the covers I’m happy and the images of the lush landscape that I saw during the day keep following me – a welcome change from the arid land surrounding the Operndorf. Here in the southwest of Burkina Faso water is plentiful and the land is green, rice grows on fields and sugar cane, papaya and mango trees, teak and eucalyptus. Palm trees are scattered through the landscape, the lakes are full with fish and at the river banks there are frogs galore. And while the geckos climb behind he pictures on the walls and clack, I fall asleep.

29. October 2017

In the morning I finally got to visit my first African market. I was immediately swept away by the abundance of colors and textures and life. There was a “pharmacy” that offered anything needed for a traditional approach to healing - from dried lizard heads to snake skins, to gnu tails and detached horns. Following our guide through narrow covered alleys I saw men sitting at sewing machines and standing on ironing boards, in small dimly lit sheds, the walls lined with black plastic garbage bags. Small iron shacks in pink and green, their “windows” unfolded upwards and secured. Outside, at the stand of a cheap jack, who announced the deal of the day with a megaphone, women in the most colorful outfits with differently patterned scarves slung around their hips and shoulders and heads, carrying babies on their backs or in front of them, were rummaging through piles of equally colorful fabrics. It was a celebration of colors and patterns and textures and I jumped right into it. For a short moment we were all just women searching for something that would make us look good. This was leisure time. I realized that this was the only time I had seen women leisurely. In all the pictures that I had taken, the images I had seen so far, the women were working. They were balancing loads on their heads, stomping the grains with huge pestles in oversize mortars, slugging water from fountains in buckets and vast yellow canisters, sweeping the grounds and tending to the fields. They ventilate the rice, pestle the millet, they dry their crop on top of the huts, they store it or sell it or cook it, they fight the dust outside and inside, they get the water in the morning and do the laundry at the fountain, they collect the wood needed for heating the fire to cook and they carry loads on their heads while balancing bicycles with babies bound to their backs or walking with their chins up to not spill anything. And they give birth over and over again and raise children, boys and girls to repeat the cycle.

Even at the Operndorf the girls seem to do all the work. Only education can break this cycle. Only education can provide change.

It was good to see a different side of Burkina Faso. When we arrive back in Ouagadougou it is almost nightfall. The city is a horizontal compilation of dust and debris. A woman is sweeping a corner on the side of the road, where she set up shop, surrounded by chaos and disarray, she doesn’t give up and she doesn’t give in but goes ahead with her business, the way she wants it done, determined and strong willed, not to be deterred by circumstances, or by the futility of her exertion. A bunch of green Mercedes 190, the taxis of Ouaga, line up on the side of a road. When they were built in Germany in the early 80ties, material exhaustion was not yet factored in. These cars were built to last a lifetime. But people want new things. Spanking shiny stuff. And so we ship them, like all the things we don’t want anymore in the West, old cars and nylon soccer uniforms and backpacks with outdated pop culture references via China to Africa where people are too poor to throw away what they don’t like. And so the kids of Burkina Faso, in the Operndorf, too, wear T-shirts with “Borussia” printed on them, not even in the right colors, or “Bayern München” or “Messi”, “Ronaldo” or “Scholl”. It does not mean anything to them and it doesn’t have to mean anything. Neither does the Prada logo on the potter’s maroon colored shirt who will burn the tiles for Claus’ project.

In the light of the sinking sun everything gleams as if someone brushed over it with burnt sienna. And as always here, as you look closer another layer is revealed. At restaurants and bars tables and chairs are arranged neatly to face the streets. Customers are awaited. The air suddenly tingles, the prospect of nightlife is palpable. Life does not stop because it gets dark. People keep moving, walking and riding their bikes and scooters. In all its improvised construction, its barely holding up and sticking together, I can see determination and an “I dare you” and “I’m here”. The clothes of the women riding on their scooters are laundered and starched and their nails and their hair are done. How much effort does it take to look like this, here where the earth is red and the air filled with its dust. They sit on their scooters racing though the streets, into the night. They are part of how the world moves.

Jeannette Mohr (*born 1961 in Nuremberg, lives in San Diego, California and Düsseldorf) studied theatre, German literature, art history and philosophy in San Diego, Berlin and Erlangen. During and after her studies she worked as a dramaturg and a director at the Oldenburg State Theatre. She then worked as a writer and producer in film and television. Since 1992 she has lived with interruptions in the United States and taught at the UCSD (University of California San Diego) in the fields of linguistics and literature up to mid-2017.

#1 January 1st - 8th Jacob Wren

#2 January 9th - 15th Toshiki Okada – japanese version

#3 January 16th - 22nd Nicoleta Esinencu – romanian version

#4 January 20th - 30th Alexander Karschnia & Noah Fischer

#5 January 30th - February 6th Ariel Efraim Ashbel

#6 February 6th - 12th Laila Soliman

#7 February 13th - 19th Frank Heuel – german version

#9 February 26th - March 5th Gina Moxley

#10 March 6th - 12th Geoffroy de Lagasnerie – version française

#11 March 13th - 19th Agnieszka Jakimiak

#12 March 20th - 26th Yana Thönnes

#13 March 30th - April 2nd Geert Lovink

#14 April 3rd - 9th Monika Klengel – german version

#15 April 10th - 16th Iggy Lond Malmborg

#16 April 17th - 23rd Verena Meis – german version

#17 April 24th - 30th Jeton Neziraj

#20 May 15th - 21st Bojan Jablanovec

#21 May 22nd - 28th Veit Sprenger – german version

#22 May 29th - June 4th Segun Adefila

#23 June 5th - 11th Agata Siniarska

#25 June 19th - 25th Friederike Kretzen – german version

#26 June 26th - July 2nd Sahar Rahimi

#27 July 3rd - 9th Laura Naumann – german version

#28 July 10th - 16th Tom Mustroph – german version

#29 July 17th - 23rd Maria Sideri

#30 July 24th - 30th Joachim Brodin

#33 August 14th - 20th Amado Alfadni

#35 August 28th - September 3rd Katja Grawinkel-Claassen – german version

#38 September 18th - 24th Marcus Steinweg

#43 October 23rd - 29th Jeannette Mohr

#44 May/December Etel Adnan

#45 December 24th - 31st Bini Adamczak

#21 May 22nd - 28th Veit Sprenger – german version

10.6. #future politics No3 Not about us Without us FFT Juta

Geoffroy de Lagasnerie Die Kunst der Revolte

21.1. #future politics No1 Speak TRUTH to POWER FFT Juta

Mark Fisher

We are deeply saddened by the devastating news that Mark Fisher died on January 13th. He first visited the FFT in 2014 with his lecture „The Privatisation of Stress“ about how neoliberalism deliberately cultivated collective depression. Later in the year he returned with a video-lecture about „Reoccupying the Mainstream" in the frame of the symposium „Sichtungen III“ in which he talks about how to overcome the ideology of capitalist realism and start thinking about a new positive political project: „If we want to combat capitalist realism then we need to be able to articulate, to project an alternative realism.“ We were talking about further collaboration with him last year but it did not work out because Mark wasn’t well. His books „Capitalist Realism“ and „The Ghosts of my Life. Writings on Depression, Hauntology and Lost Future“ will continue to be a very important inspiration for our work.

Podiumsgespräch im Rahmen der Veranstaltung "Die Ästhetik des Widerstands - Zum 100. Geburtstag von Peter Weiss"

A Collective Chronicle of Thoughts and Observations ist ein Projekt im Rahmen des Bündnisses internationaler Produktionshäuser, gefördert von der Beauftragten der Bundesregierung für Kultur und Medien.